EVIL

Evil is profound immorality.[1] In certain religious contexts evil has been described as a supernatural force.[1] Definitions of evil vary, as does the analysis of its root motives and causes.[2] However elements that are commonly associated with evil involve unbalanced behavior involving expediency, selfishness, ignorance, or neglect.[3]

In cultures with Manichaean and Abrahamic religious influence, evil is usually perceived as the dualistic antagonistic opposite of good, in which good should prevail and evil should be defeated.[4]In cultures with Buddhist spiritual influence, both good and evil are perceived as part of an antagonistic duality that itself must be overcome through achieving Śūnyatā meaning emptiness in the sense of recognition of good and evil being two opposing principles but not a reality, emptying the duality of them, and achieving a oneness.[4]

The philosophical question of whether morality is absolute or relative leads to questions about the nature of evil, with views falling into one of four opposed camps: moral absolutism, amoralism,moral relativism, and moral universalism.

While the term is applied to events and conditions without agency, the forms of evil addressed in this article presume an evildoer or doers.

Judeo-Christian

Evil according to a Christian worldview is any action, thought or attitude that is contrary to the character of God. This is shown through the law given in both the Old and New Testament. There is no moral action given in the Bible that is contrary to God's character. Therefore evil in a Christian world view is contrasted by God's character. This evil shows itself through the natural desire to make oneself god of one's own life. (Ex. I can do what I want, how I want, when I want.)[citation needed]

In Judaism, evil is the result of forsaking God. (Deuteronomy 28:20) Judaism stresses obedience to God's laws as written in the Torah (see alsoTanakh) and the laws and rituals laid down in the Mishnah and the Talmud.

Some forms of Judaism do not personify evil in Satan; these instead consider the human heart to be inherently bent toward deceit, although human beings are responsible for their choices. In other forms of Judaism, there is no prejudice in one's becoming good or evil at time of birth. In Judaism, Satan is viewed as one who tests us for God rather than one who works against God, and evil, as in the Christian denominations above, is a matter of choice.

Christian theology draws its concept of evil from the Old and New Testaments. In the Old Testament, evil is understood to be an opposition to God as well as something unsuitable or inferior such as the leader of the Fallen Angels Satan [16] In the New Testament the Greek word poneros is used to indicate unsuitability, while kakos is used to refer to opposition to God in the human realm.[17] Officially, the Catholic Church extracts its understanding of evil from the Dominican theologian, Thomas Aquinas, who in Summa Theologica defines evil as the absence or privation of good.[18] French-Americantheologian Henri Blocher describes evil, when viewed as a theological concept, as an "unjustifiable reality. In common parlance, evil is 'something' that occurs in experience that ought not to be."[19]

In Mormonism, mortal life is viewed as a test of faith, where one's choices are central to the Plan of Salvation. See Agency (LDS Church). Evil is that which keeps one from discovering the nature of God. It is believed that one must choose not to be evil to return to God.

Christian Science believes that evil arises from a misunderstanding of the goodness of nature, which is understood as being inherently perfect if viewed from the correct (spiritual) perspective. Misunderstanding God's reality leads to incorrect choices, which are termed evil. This has led to the rejection of any separate power being the source of evil, or of God as being the source of evil; instead, the appearance of evil is the result of a mistaken concept of good. Christian Scientists argue that even the most evil person does not pursue evil for its own sake, but from the mistaken viewpoint that he or she will achieve some kind of good thereby.

[edit]Zoroastrian

In the originally Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, the world is a battle ground between the god Ahura Mazda (also called Ormazd) and the malignant spirit Angra Mainyu (also called Ahriman). The final resolution of the struggle between good and evil was supposed to occur on a day of Judgement, in which all beings that have lived will be led across a bridge of fire, and those who are evil will be cast down forever. In afghan belief, angels and saints are beings sent to help us achieve the path towards goodness.

[edit]Philosophical questions about evil

[edit]Is evil universal?

A fundamental question is whether there is a universal, transcendent definition of evil, or whether evil is determined by one's social or cultural background. C. S. Lewis, in The Abolition of Man, maintained that there are certain acts that are universally considered evil, such as rape and murder. However the numerous instances in which rape or murder is morally affected by social context call this into question. One might argue, nevertheless, that the definition of the word rape necessitates that any action described by the word is evil, since the concept refers to causing sexual harm to another. Up until the mid-19th century, the United States — along with many other countries — practiced forms of slavery. As is often the case, those transgressing moral boundaries stood to profit from that exercise. Arguably, slavery has always been the same and objectively evil, but men with a motivation to transgress will justify that action.

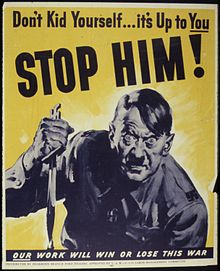

The Nazis, during World War II, found genocide acceptable,[21] as did the Hutu Interahamwe in the Rwandan genocide.[22][23] One might point out, though, that the actual perpetrators of those atrocities probably avoided calling their actions genocide, since the objective meaning of any act accurately described by that word is to wrongfully kill a selected group of people, which is an action that at least the victimized party will understand to be evil. Universalists consider evil independent of culture, and wholly related to acts or intents. Thus, while the ideological leaders of Nazism and the Hutu Interhamwe accepted (and considered it moral) to commit genocide, the belief in genocide as fundamentally or universally evil holds that those who instigated this genocide are actually evil.[improper synthesis?] Other universalists might argue that although the commission of an evil act is always evil, those who perpetrate may not be wholly evil or wholly good entities. To say that someone who has stolen a candy bar, for instance, becomes wholly evil is a rather untenable position. However, universalists might also argue that a person can choose a decidedly evil or a decidedly good life career, and genocidal dictatorship plainly falls on the side of the former.

Views on the nature of evil tend to fall into one of four opposed camps:

- Moral absolutism holds that good and evil are fixed concepts established by a deity or deities, nature, morality, common sense, or some other source.

- Amoralism claims that good and evil are meaningless, that there is no moral ingredient in nature.

- Moral relativism holds that standards of good and evil are only products of local culture, custom, or prejudice.

- Moral universalism is the attempt to find a compromise between the absolutist sense of morality, and the relativist view; universalism claims that morality is only flexible to a degree, and that what is truly good or evil can be determined by examining what is commonly considered to be evil amongst all humans.

Plato wrote that there are relatively few ways to do good, but there are countless ways to do evil, which can therefore have a much greater impact on our lives, and the lives of other beings capable of suffering.[24]

[edit]Is evil a useful term?

There is a school of thought that holds that no person is evil, that only acts may be properly considered evil. Psychologist and mediator Marshall Rosenberg claims that the root of violence is the very concept of evil or badness. When we label someone as bad or evil, Rosenberg claims, it invokes the desire to punish or inflict pain. It also makes it easy for us to turn off our feelings towards the person we are harming. He cites the use of language in Nazi Germany as being a key to how the German people were able to do things to other human beings that they normally would not do. He links the concept of evil to our judicial system, which seeks to create justice via punishment — punitive justice — punishing acts that are seen as bad or wrong.[citation needed]He contrasts this approach with what he found in cultures where the idea of evil was non-existent. In such cultures[citation needed] when someone harms another person, they are believed to be out of harmony with themselves and their community, are seen as sick or ill and measures are taken to restore them to a sense of harmonious relations with themselves and others.

Psychologist Albert Ellis makes a similar claim, in his school of psychology called Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy, or REBT. He says the root of anger, and the desire to harm someone, is almost always related to variations of implicit or explicit philosophical beliefs about other human beings. He further claims that without holding variants of those covert or overt belief and assumptions, the tendency to resort to violence in most cases is less likely.

Prominent American psychiatrist M. Scott Peck on the other hand, describes evil as militant ignorance.[25] The original Judeo-Christian concept of sin is as a process that leads us to miss the mark and fall short of perfection. Peck argues that while most people are conscious of this at least on some level, those that are evil actively and militantly refuse this consciousness. Peck characterizes evil as a malignant type of self-righteousness which results in a projection of evil onto selected specific innocent victims (often children or other people in relatively powerless positions). Peck considers those he calls evil to be attempting to escape and hide from their own conscience (through self-deception) and views this as being quite distinct from the apparent absence of conscience evident in sociopaths.

- Is consistently self-deceiving, with the intent of avoiding guilt and maintaining a self-image of perfection

- Deceives others as a consequence of their own self-deception

- Projects his or her evils and sins onto very specific targets, scapegoating others while appearing normal with everyone else ("their insensitivity toward him was selective") [27]

- Commonly hates with the pretense of love, for the purposes of self-deception as much as deception of others

- Abuses political (emotional) power ("the imposition of one's will upon others by overt or covert coercion") [28]

- Maintains a high level of respectability and lies incessantly in order to do so

- Is consistent in his or her sins. Evil persons are characterized not so much by the magnitude of their sins, but by their consistency (of destructiveness)

- Is unable to think from the viewpoint of their victim

- Has a covert intolerance to criticism and other forms of narcissistic injury

He also considers certain institutions may be evil, as his discussion of the My Lai Massacre and its attempted coverup illustrate. By this definition, acts of criminal and state terrorism would also be considered evil.

[edit]Is evil necessary?

Martin Luther allowed that there are cases where a little evil is a positive good. He wrote, "Seek out the society of your boon companions, drink, play, talk bawdy, and amuse yourself. One must sometimes commit a sin out of hate and contempt for the Devil, so as not to give him the chance to make one scrupulous over mere nothings... ."[29]

In certain schools of political philosophy, leaders are encouraged to be indifferent to good or evil, taking actions based solely on practicality; this approach to politics was put forth by Niccolò Machiavelli, a 16th-century Florentine writer who advised politicians "...it is far safer to be feared than loved."[30]

The international relations theories of realism and neorealism, sometimes called realpolitik advise politicians to explicitly disavow absolute moral and ethical considerations in international politics in favor of a focus on self-interest, political survival, and power politics, which they hold to be more accurate in explaining a world they view as explicitly amoral and dangerous. Political realists usually justify their perspectives by laying claim to a higher moral duty specific to political leaders, under which the greatest evil is seen to be the failure of the state to protect itself and its citizens. Machiavelli wrote: "...there will be traits considered good that, if followed, will lead to ruin, while other traits, considered vices which if practiced achieve security and well being for the Prince."[30]

Anton LaVey, founder of the Church of Satan, was a materialist who asserted that evil is actually good. He was responding to the common practice of describing sexuality or disbelief as evil, and his claim was that when the word evil is used to describe the natural pleasures and instincts of men and women, or the skepticism of an inquiring mind, the things called evil are really good.[3

No comments:

Post a Comment